It wasn’t. But it is now.

The Economist | 15/01/2025

For years there has been a push to recognise obesity as a disease in its own right, and therefore something that needs to be treated in and of itself, rather than just as a risk factor for other things, such as diabetes, heart disease, strokes and some cancers. And there is indeed much evidence that being obese can result in exceptionally poor health. But many who are obese are not unwell in the slightest. This argues that obesity per se should not be treated as an illness.

Until two years ago, such discussion was of little practical relevance since there were few treatments for obesity between the extremes of bariatric surgery and the old-fashioned approach of eating less and exercising more. However, the arrival in 2023 of GLP-1 weight-loss drugs in the form of semaglutide (known commercially as Wegovy) changed that. If these drugs are to be prescribed sensibly and fairly, then who among the fat is sick and who is not becomes an important question.

By coincidence (they started before GLP-1 drugs were approved for slimming), a group of 56 doctors have just answered that question. This group, called the Lancet Commission, and organised by the journal of that name, have developed a better way of diagnosing obesity—one that distinguishes when it has become pathological.

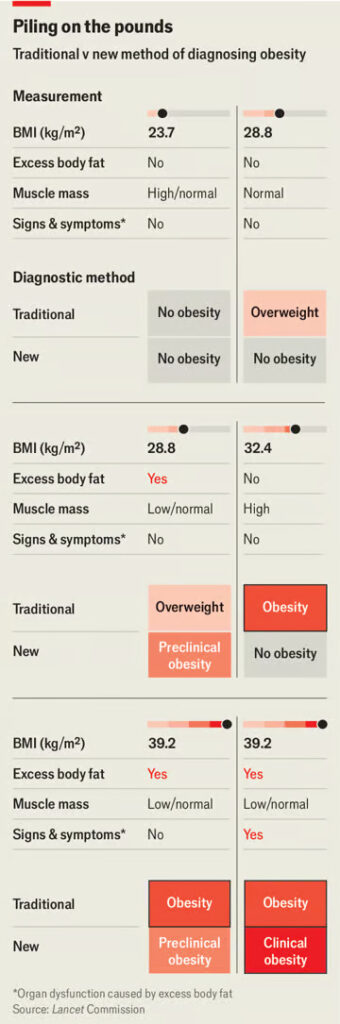

The usual current measure of obesity is body mass index (BMI). This has the advantage of being easily calculated (by dividing a person’s weight in kilograms by the square of their height in metres). Obesity is then defined as a BMI of more than 30. But some people with a high BMI show no signs of being unwell. And, absurdly, stocky and well-muscled athletes have been known to qualify as obese according to this classification. Nor does BMI take account of fat’s bodily distribution. Yet it is well established that visceral fat (stored around the internal organs, for an “apple-shaped” body), is far more unhealthy than subcutaneous fat (stored directly under the skin, for a “pear-shaped” one). The commission’s recommendations, though, take care of these points.

To diagnose their newly defined disease, which they call “clinical obesity”, the commissioners require two things. First, the addition of a third measure of body size (waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio or waist-to-height ratio) to those used to calculate BMI—though measuring body fat directly, with sophisticated modern scanning tools is even better.

Second, if this revised measurement does, indeed, proclaim an individual to be obese, some objective signs and symptoms of reduced organ function, or ability to conduct daily activities—such as bathing, eating and dressing—are also needed to declare that obesity to be clinically relevant.

The 18 diagnostics the commissioners have lit on include breathlessness, obesity-induced heart failure, knee or hip pain, and obesity-driven signs of dysfunction in many other organs, such as the liver, heart, kidneys and urinary and reproductive systems. Those without these symptoms are not let off scot-free. They are assigned to a limbo called “preclinical obesity” since, though not ill, they are reckoned to have an increased risk of developing clinical obesity and thus becoming so. But they are not candidates for immediate drug treatment.

Francesco Rubino, a professor in metabolic and bariatric surgery at King’s College, London, who is also one of the commissioners, reckons describing obesity as an actual disease is quite a radical shift. The next task—one which others have already started, he says—is to work out who among the 1bn or so people on the planet who were classified as obese according to the old definition qualify as being clinically obese under the new one, and thus in need of treatment. Preliminary work, he says, suggests 20-40% of them.

The commission’s approach already seems popular with medical officialdom. Seventy-six of the world’s leading health organisations, including the American Heart Association, the Chinese Diabetes Society and the All Indian Association for Advancing Research in Obesity, have already endorsed it. How quickly it will percolate into medical practice and public perceptions of who is and is not dangerously obese is another matter.

Published by The Economist

https://www.economist.com/science-and-technology/2025/01/15/is-obesity-a-disease