Opinion by Beatriz Rey and Will Freeman at Miami Herald | 11/05/2023

Brazil’s President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva started his administration with two bold promises to fight climate change: achieve zero deforestation and reduce illegal mining in the Amazon. But despite Lula’s commitment to green politics, the Amazon issue remains unresolved.

Recently, eight bodies were found as a result of conflicts involving illegal miners and organized crime in an indigenous reserve in the region. This is not the first such occurrence this year.

The government faces opposition from the congressional agribusiness caucus, which has dismantled environmental policies during former President Jair Bolsonaro’s tenure and is now the biggest threat to a green agenda. Given the importance of the agribusiness sector for the country’s economy, implementing pro-environment policies without its support becomes a daunting task.

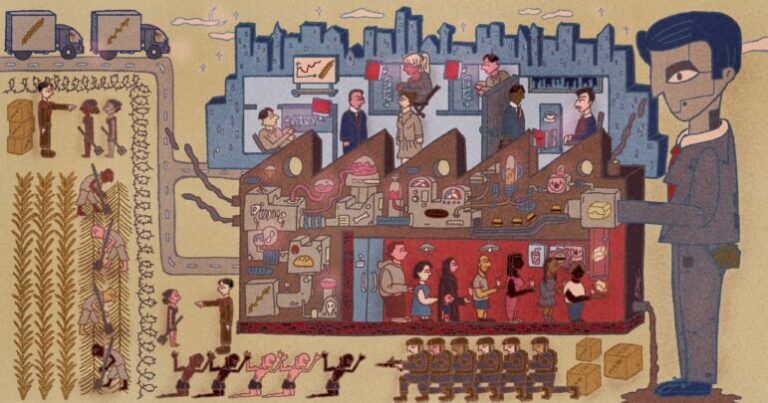

The agribusiness caucus is an organization of legislators from different political parties that defends the interests of landowners and rural producers. It dates back to 1988, when a group of landowner lawmakers organized to ensure their interests were represented in the Constitutional Assembly.

Since then, the caucus has behaved as a quasi-party, defending lax environmental and land regulation. Its members meet weekly at their own building to discuss strategies and bills to strengthen the sector. It also has its own news agency, Agência FPA, and think tank, Pensar Agro Institute. Pensar Agro has been funded by agribusiness interest groups to provide technical and logistical support to its members, which are crucial for their success in approving or blocking bills in Brazil’s Congress. These interest groups have even financed some of Brazil’s top musicians to create a new genre of hit music, Agronejo, to promote its pro-business, anti-green agenda.

Bolsonaro empowered the caucus as soon as he was elected in 2018, choosing the caucus president as the minister of agriculture. He selected an anti-environment politician who largely eased off environmental and land regulations and protections as minister of the environment. As a result, an area the size of the state of Rio de Janeiro — slightly larger than Maryland — was deforested in the Amazon under his administration.

Environmental fines also dropped by 35% as Bolsonaro understaffed the federal bureaucracies responsible for oversight. The average spending of his Ministry of the Environment was the lowest recorded in the past six administrations.

Fortunately, Lula has shifted gears since taking office, starting with his picks for the ministers of agriculture and the environment — both aligned with his pro-environment agenda. However, he faces a newly empowered agribusiness caucus interested in blocking or stalling any environmental policy.

The caucus has pushed for a restructuring of Brazil’s government ministries, which would curb the state’s ability to stop deforestation and mining on indigenous reservations. It has threatened to mobilize its members in Congress to block government initiatives if Lula does not recognize it as a key stakeholder.

Lula has tried to build bridges. For instance, he included representatives from the sector as part of his entourage that visited China in March. However, the climate between the government and the caucus has further deteriorated after the landless movement (a government ally) recently invaded several farms. Concerned about the agribusiness opposition in the legislative arena, a senator from Lula’s party has recently asked permission to attend the caucus’ weekly meetings in an attempt to promote reconciliation. It is unclear whether he will be successful.

As Lula struggles to implement his agenda, international pressure could push the caucus toward a more friendly environmental approach. For instance, an environmental law organization recently filed a formal complaint against Cargill, the world’s largest grain trader, for its failure to remove deforestation abuses from its Brazilian soya supply chain.

The agribusiness sector cares about Brazil’s image abroad among export markets. The United States and other countries should continue to invest in the Amazon, but also impose costs for trading with an anti-green agribusiness sector.

There’s reason to leverage this angle: The caucus itself has strongly condemned any association between its work and deforestation. While it is unlikely that it will ever accept full environmental and land protections, the right incentives might lead it to at least engage in fruitful dialogues with the government.

That would be a good start.

Beatriz Rey is a senior researcher at the State University of Rio de Janeiro.

Will Freeman is a Latin America Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

First published in Miami Herald

https://www.miamiherald.com/opinion/op-ed/article275222091.html