Career consultant, Visiting Professor at Imperial College London and CIWM Past President, David C. Wilson, introduces his witness account of the evolution of waste and resource management since then and reflects on future directions and priorities

By David C. Wilson in Resource | 20/11/2024

2024 marks 50 years since the UK’s first environmental control legislation, the Control of Pollution Act 1974 (C0PA); other countries enacted similar legislation around the same time. This was a momentous first step, introducing legal controls over recovery and disposal without which the waste and resources sector as we know it simply would not exist. I happened to start my first job in the sector at the old Harwell Laboratory a week after CoPA was enacted, and recently published my magnum opus documenting the rapid and massive evolution of waste and resource management worldwide since then. But we do need to remember that critical first step – it was not so very long ago! There is still much to do, and unless we understand how the sector has developed we cannot plan effectively for the future. So, whither next?

Evolution of solid waste management into waste and resource management

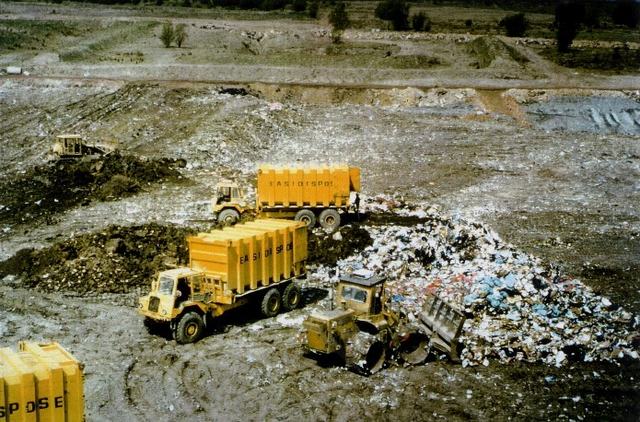

The two ladders in Figure 1 help us to understand how municipal solid waste management (MSWM) has evolved. They show (a) stepwise progression of service levels for waste collection and (b) of control levels for recovery and disposal. The UK baseline in 1970 was already near 100% basic collection service of mixed waste ; but with no or limited control over disposal. So, the initial priority of CoPA was to set standards for basic levels of controlled recovery and disposal (Figure 1b). I label the response as the ‘technical fix’; what mix of technologies can meet the legal standards at least cost? Figure 2 shows a model 1970s UK controlled landfill, achieving operational control through the ‘3Cs’ – confine within a cell, compact and cover.

Figure 1. Evolutionary ladders for municipal solid waste management

Figures © Andrew Whiteman and David C. Wilson

Figure 2. 1970s best practice controlled landfill for municipal solid waste

Photo: David Campbell

By 1980, the UK had largely reached the basic control standards initially set under CoPA, so standards began to be ramped up in a series of steps, e.g. on landfill leachate and gas control, moving through improved to full control (Figure 1b) during the 1980s and beyond. Full control or environmentally sound management (ESM) was eventually required in the UK when the EU Incineration Directive was implemented in 1996 and the Landfill Directive in 2003.

By the 1990s, people were beginning to recognise that the technical fix, based on technologies within a strictly enforced legislative framework, was not sufficient on its own. This led to a new paradigm, integrated sustainable (solid) waste management (ISWM), a simplified version of which is shown in Figure 3.. The first triangle shows technical factors, the ‘hard’ components required for physical management of wastes, the ‘what to do’. The second shows ‘soft’ or ‘governance’ aspects, required to make that happen in practice, the ‘how to do it’: inclusivity of stakeholders (particularly service users and providers); financial sustainability; and sound institutions and pro-active policies at both national and local level.

Figure 3. The simplified ‘two triangles’ representation of the Integrated Sustainable Waste Management (ISWM) framework

© David Wilson, Costas Velis, Ljiljana Rodic

In the UK and elsewhere in the Global North, new landfill and incineration facilities to meet full control ESM standards had become increasingly expensive by the 1990s, and beyond the technical capacity of (small) municipal governments. Attempts to achieve economies of scale through inter-municipal co-operation or amalgamation, and to access technical capacity through contracting out to the private sector, likely exacerbated strong local opposition to new mega-facilities (not in my back yard – NIMBY). Also, the 1991 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change made methane from landfill into a climate issue.

There are three physical components of ISWM shown in Figure 3, each linked to a primary driver. Prior to any legislation, the main driver was the resource value in the waste, so cities early in the nineteenth century had a thriving informal repair, reuse and repair sector. Successive UK Public Health Acts from 1848 focussed on waste collection, which combined with rising living standards and cheap consumer goods had left municipal solid waste (MSW) recycling rates by 1970 below 5%. The new environment driver from the 1970s forced costs up, so since the 1990s recycling, of both dry materials and composting or anaerobic digestion of wet, putrescible organics such as food and garden wastes, has been rediscovered, not so much as a source of revenue but more as an alternative, potentially cheaper waste destination or ‘sink’.

To achieve a step change in recycling rates, it has been necessary to move beyond the basic service level of (mixed) waste collection in Figure 1a, collecting two, three or more separated fractions. This in turn has required more focus on the soft, governance aspects in Figure 3, including changing behaviour of service users and providing a balanced basket of policy instruments, which in the UK has centred around steadily increasing levels of landfill tax to achieve both recycling and landfill diversion targets. Solid waste management (SWM) was evolving into waste and resource management (WaRM).

The Global South

The 1970s baseline in the Global South was lower. Waste collection in larger cities was around 30-60% (focused on central business districts and richer residential areas); with most collected waste going to municipal dumpsites that were often on fire. However, recycling rates were often much higher than in the Global North thanks to an active informal sector, particularly in parts of Asia.

There has been considerable progress, particularly in upper- and middle-income countries which have more capacity to address the institutional and financial constraints. Attempts to export technologies designed for American, European or Japanese wastes, regulatory systems, cultures and income levels, have often resulted in failure; unfortunately, such mistakes are still being repeated. Our current best estimate is that 2-3 billion people still lack access to a waste collection service; with another billion lacking access to controlled recovery and disposal facilities. This is an on-going global waste emergency which requires concerted, urgent action.

Reflections on the future – to 2030 and beyond

Priority Challenges

Understanding this evolution of waste and resource management over the last 50 years is important when looking forward. The waste problem has absolutely not been ‘solved’. Even in the Global North, much remains to be done, moving beyond environmentally sound management and recycling towards waste prevention and a truly circular economy. It is important to remember that the waste and resource management sector as we know it only exists due to strong and effectively enforced legislation; creating a ‘level playing field’ to attract investment in higher standard facilities and practices, without fear of being undercut by other facilities operating to lower standards or indeed by waste criminals. Challenges include achieving clean ‘cycles’ which avoid the accumulation of hazardous substances, recognising both limits to recycling and the continuing need for final sinks; and ‘new’ waste streams, e.g. electric car batteries, solar panels etc, for which both 3Rs (reduce, reuse, recycle) and ESM approaches have yet to be (fully) developed.

The priority in much of the Global South remains to bring wastes under control: to extend MSW collection to all and phase out uncontrolled dumpsites and open burning (achieving SDG indicator 11.6.1).

New Opportunities

For most of my career, waste management has been the forgotten utility service, taken for granted until something goes wrong; a ‘Cinderella’ topic low on the political agenda. Now, three international negotiations may just provide a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to change that, and to put waste and resource management properly on the international agenda.

First are the annual climate COPs. Waste and resource management is on the agenda for the first time at COP29 in Baku, with a Declaration on Reducing Methane from Organic Waste. Second, the proposed Plastics Treaty, which needs to focus BOTH on reductions in production and single-use, AND on proper waste management; a recent Nature paper showed that meeting SDG 11.6.1 worldwide (i.e. tackling the global waste emergency) would reduce macroplastics pollution by 85%. Third, establishing an international science-policy panel on chemicals, waste and pollution prevention (SPP), modelled on the IPCC for climate change. However, there is much work to be done to ensure that these opportunities are grasped.

Three key policy priorities for all countries

Sustainable financing

Sustainable financing remains a challenge for both residual waste management and recycling facilities, particularly in countries like the UK and US which rely more on market forces. ‘Regulatory certainty’ is critical for investor confidence; a current case in point is the announced closure of Viridor’s 2022 Avonmouth mechanical polymers recycling plant, due in part to delays in implementing England’s 2018 Waste and Resources Strategy.

In much of the Global South, the financial costs of even basic services for MSWM are unaffordable locally, but the economic benefits of reducing plastics pollution and mitigating global heating are felt worldwide; so a global initiative is required to develop tailored and innovative financing mechanisms (including ‘climate’ and ‘plastics’ finance as well as EPR, see below) to extend services to under-served communities.

Rethink sustainable recycling

In the Global North, the MSW recycling system, which has been rebuilt from a low base over the past 30 years, is broken. Focus needs to shift from increasing the supply of materials, as measured by quantities collected for recycling, to increasing demand and the quality and quantity of materials actually recycled. Targets need to be set not just on weight, but also on carbon.

In the Global South, the baseline is quite different, with active informal sector recycling often operating in parallel to formal city MSWM. Here, rethinking means first, combining existing formal MSWM and informal recycling into one integrated WaRM system and involving informal recyclers as a key stakeholder group. Second, moving early to leapfrog the ‘basic’ level of collection service, going directly to an ‘improved’ or ‘full’ level of service collecting two, three or more source segregated fractions (Figure 1a). The benefits should be a win-win-win: extended collection coverage; less waste requiring controlled disposal so less investment required; and more jobs with better working conditions for both formal and informal waste workers.

EPR with teeth

An ever increasing proportion of MSW comprises packaging and end-of-first-life consumer products; why should the responsibility for managing those wastes fall to the local authority rather than the ‘producers’ (manufacturers and supply chain) who place them on the market? Such extended producer responsibility (EPR) was introduced in Europe from the 1990s, but implementation has varied widely. In the UK, EPR reimbursed only 10% of local authority costs in managing packaging wastes; hence proposals in England’s Waste and Resource Strategy 2018 for ‘EPR2.0’, but these have yet to be implemented.

The idea is sound, but to work effectively EPR needs to be given ‘teeth’ rather than just ‘gums’. The producers need to cover all the end-of-first-life costs; meet progressively increasing recycling targets; and take full responsibility to ensure that recycling both can and does take place in an environmentally sound (ESM) way – thus avoiding disasters like the new Viridor polymer recycling plant going bust. Well-designed EPR schemes must also incentivise product design to reduce waste quantities; facilitate disassembly for easy repair, reuse, and recycling; and minimise use of difficult-to-recycle materials and chemical substances of concern.

MSW in lower income countries also contains significant packaging and end-of-life products – that which they cannot afford to collect or manage properly accounts for 85% of global macroplastic pollution. Therefore EPR must be extended worldwide. Many lower income countries have a GDP less than the revenue of a large transnational corporation; so EPR needs to be implemented in a coordinated way across the world, with regional or even global mechanisms for negotiation. Such EPR systems need careful and innovative design, to ensure that funds and other support reach both municipalities where MSW is currently uncollected and mismanaged, and informal recyclers to help them extend their activities beyond materials such as PET bottles for which in many locations there is already a market.

Extending waste services to all

Implementation of these three priority policies would already go a long way to addressing the global waste emergency of billions of people still without even basic MSWM services. However, the traditional ‘top-down’ approach to development, working through national governments, gradually building capacity, and focusing on (larger) investments in infrastructure, will take many years to reach the poorest communities. So a parallel, complementary, ‘bottom-up’ approach is also required, working with NGOs and communities themselves, and putting people at the centre of the narrative. Sustainable waste and resource management needs to work for the poorest people, providing both a quality service which keeps low-income and slum areas clean and healthy, and a decent livelihood for the multitude of workers who deliver collection and recycling services and EPR on behalf of producers (Figure 4).

Figure 6. A people-centred approach to municipal solid waste management services Images of formal and

informal professional service providers, Sasmita and S.K., and a resident in Dhenkanal, Odisha State, India.

Photo Credit: Shreeyanka Chowdhury, © Practical Action, reproduced with permission.

In Conclusion

When I first stumbled into waste management in 1974, I did not expect still to be here 50 years later. The constantly evolving challenges and opportunities are greater now than ever; the early 2020s may be a ‘tipping point’, when my ‘baby’ has ‘come of age’ and is emerging at last onto the world stage as a global priority. But I do need to continue handing on the baton to the next generations of waste and resource management practitioners: I have written my ‘contemporary witness’ account for you. Please do download and dip into it – I hope you find inspiration.

You can download David C. Wilson’s magnum opus, ‘Learning from the past to plan for the future: An historical review of the evolution of waste and resources management 1970-2020 and reflections on priorities 2020-2030 – The perspective of an involved witness’

David C Wilson on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/profdcw/

Published in Resource.co

https://resource.co/article/marking-50-years-first-control-pollution-act-1974